The Sensible Wash Their Socks at Night

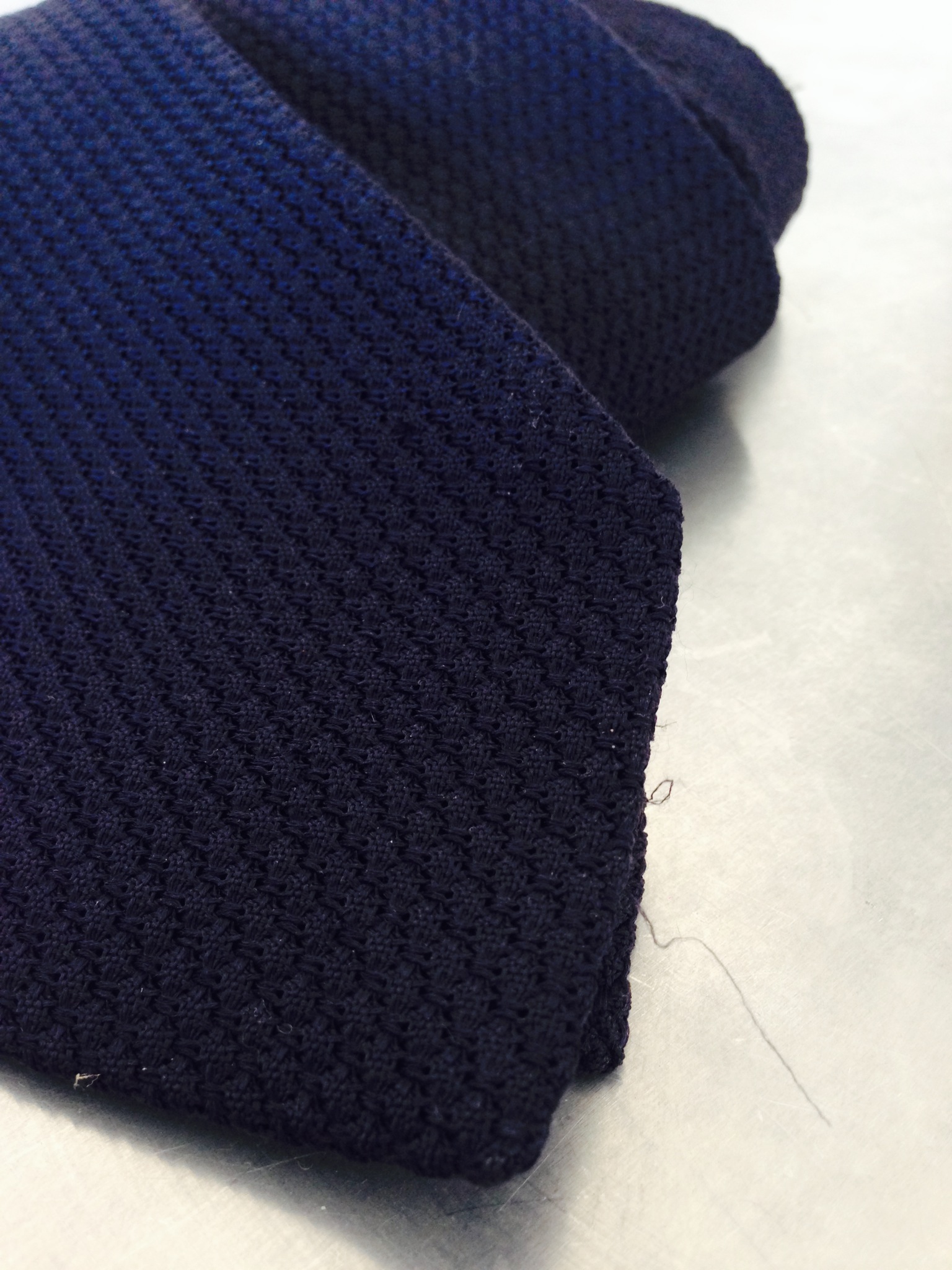

From left: cotton mesh, lightweight wool, silk, and heavy merino.

Socks are the single wrench in the workings of an otherwise good marriage. I already handle my shirts—laundering, line-drying and hand-pressing—and what little dry-cleaning I do is accomplished a few times each year with the help of a very small business and a very large dose of faith. I don’t believe in precious athletic clothes and underwear, so mine get heaped in with the general population. This leaves socks, an innocent sounding statement that might as well read: this leaves air, or, this leaves purpose.

Why do socks inhabit so precious a place? Imagine, for a moment, a young boy. He is an active boy, but also an observant one. One who climbs old fir trees and scraps with the neighborhood toughs, but also watches carefully as his father ties his tie and laces his shoes. He can’t say why, but his clothes seem more important to him than they do for other boys his age. He gets older and his interest in clothes strengthens. Rather than suppressing his interest, he seeks edification; it comes disguised in books and movies. He makes the expected mistakes of an amateur, lured astray by the siren call of fashion magazines, but returns loyally to what he loves: classic clothing, as functional as it is handsome. His preferences calcify. He notices the small things—shirt collars that gap or pinch, trousers that bunch or bind. One day, he turns his attention to socks. He is dissatisfied with the wimpy, pooling mid-calf socks that are the department store standard. His salvation comes as a gift; a pair of socks that, because of their length, he assumes are a mistake. In a rush one day he slips them on. It is a revelation; the socks stay up, held smartly above the bulge of his calf by a gently elasticized opening. He seeks out several more pairs. Soon, he turns his attention to his trousers; in order to maximize the comfort and style of his excellent new over-the-calf socks, he begins seeking trousers with fuller legs and more precisely hemmed bottoms. The line of these trousers craves jackets with more nuance—a fuller chest, a nipped waist and a natural shoulder. This elegant silhouette deserves only classic accessories; his shirts and ties are purchased with versatility in mind and his shoes are unimpeachably correct. It is not long before his wardrobe has molded itself around his now considerable collection of quality socks.

So: it all begins with socks. Some say the shoe is the foundation of a good wardrobe; these people have obviously never had cheap socks puddled like leg warmers below their calves. It is impossible to feel stylish—let alone look it—if every few minutes attention is turned to adjusting socks. A hairy and exposed shin, it should go without saying, is also a style killer. Men used to solve this problem with garters; these held socks in place, but were fiddly and slightly too reminiscent of lingerie. Happily, elastic and knitting technologies improved, and the modern over-the-calf sock was born. The best examples today can be made of fine cotton, silk, wool and cashmere or blends in any combination. They can have texture, like ribbing, and be woven with contrasting yarns to create any of the classic menswear patterns: chalk-stripes, pinstripes, checks, plaids, herringbone and dog-tooth. Choosing correctly from this vast library deserves an essay of its own, but several pairs in a good pattern and color, say, ribbed flannel grey wool, are indispensable in dressing efficiently and, ultimately, well.

The problem with good socks is they must be carefully laundered. The danger of shrinking, running and losing is real. And so I return to how I began: if good socks are going to be worn, their maintenance is the sole responsibility of the wearer. Here is how:

Remove socks, fold together and hide from the person who ordinarily does the laundry.

Wait until 3AM; the washing machine will be vacant and the danger of someone interfering with the cycle, minimal.

Inventory your socks; a spreadsheet isn’t necessary but a pen and paper is helpful.

Verify that the machine is free of clothes; bright red shirts often lurk in its recesses, waiting to turn everything pink.

Add socks. Select the coldest, gentlest setting and launder using premium, delicate-cycle washing powder.

The instant the cycle is finished, remove socks and take inventory.

Hang in pairs on shirt hangers in a cool and airy space.

When dry, immediately fold and return to sock drawer.